PeerJ: A Tournaisian (earliest Carboniferous) conglomerate-preserved non-marine faunal assemblage and its environmental and sedimentological context

Jenny Clack, Carys Bennett, Sarah Davies, Andrew Scott, Janet Sherwin, Tim Smithson

This paper is about what we found in a single bed near the top of the sequence at Burnmouth, just north of Berwick on Tweed. The whole exposure at Burnmouth is a series of vertically-orientated beds about 500 metres wide, with the oldest rocks under the cliffs near the harbour (bottom right in the photo below), and the youngest at the east end of the cliffs to the south of the bay, (top, in the photo).

I've used a few technical terms in this summary, and where appropriate, have included a link to an explanatory page, usually in Wikipedia. This is highlighted in the text by the technical term being rendered in bold, blue text. If you click the link, it should open the target page in a new tab in your browser, leaving this page still open in its own tab.

We located the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary close to the harbour, so numbered the interesting beds using their 'height' (ie horizontal displacement) above that. Altogether we found 11 beds containing vertebrate bones, including seven containing tetrapods. The bed that is the subject of this paper is designated 'Bed 383', as it is 383 metres above the D-C boundary. Assuming (cautiously) that the beds were laid down at a more or less uniform rate, that would make this bed roughly 350 million years old, or about nine million after the end of the Devonian. Unfortunately, this, one of the most productive beds we've found at Burnmouoth, was obliterated by a large rock fall early in 2018.

Burnmouth Bay from the cliff top. © Copyright Rob Clack 2012.

The cliffs at the south end of Burnmouth. © Copyright Rob Clack, 2012

We've interpreted the exposure at Burnmouth as a series of meandering rivers, with some massive sandstone beds having been deposited by the rivers, interspersed with layers of rock called dolostone, which would have been laid down in shallow lakes, with occasional marine flooding. Most of the beds containing vertebrate remains we think are sandy siltstones, sometimes more sandy, sometimes more silty. This bed, however, is a conglomerate, which seems to have been a flood deposit, as everything is jumbled up and the lumps of matrix are clearly from a variety of different sources.

We've recovered many bones from Bed 383, all isolated, including some very large ones and some very small ones. Many examples of tetrapods, lungfishes, rhizodonts, gyracanths, actinopterygians (ray- finned fishes), and chondrichthyans (sharks and rays). Many of the bones are fragmentary, and for the most part you can't tell what they came from, although some you can identify more precisely.

The bed also contains charcoalified plant stems, charcoal fragments, and wood fragments. However, the more fragile ostracod and bivalve fossils that are a common element of many sedimentary rocks are absent.

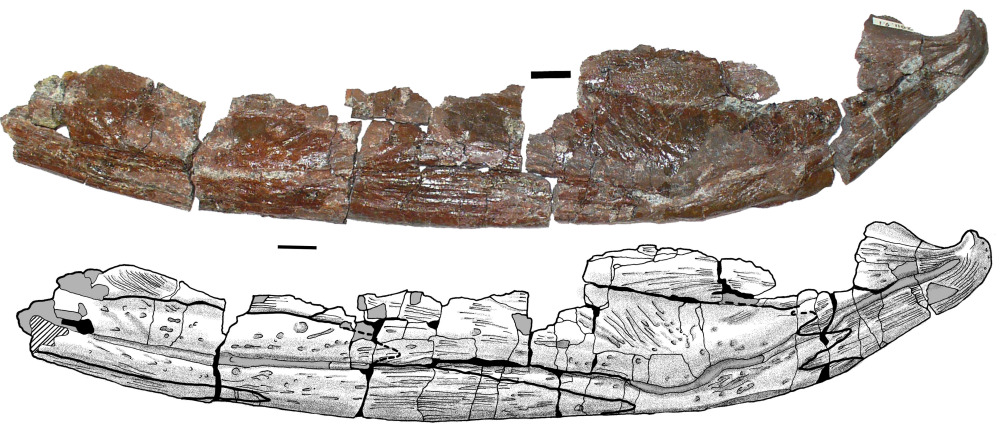

Partial lower jaw of a Crassigyrinus-like animal as found. © Copyright Rob Clack 2010

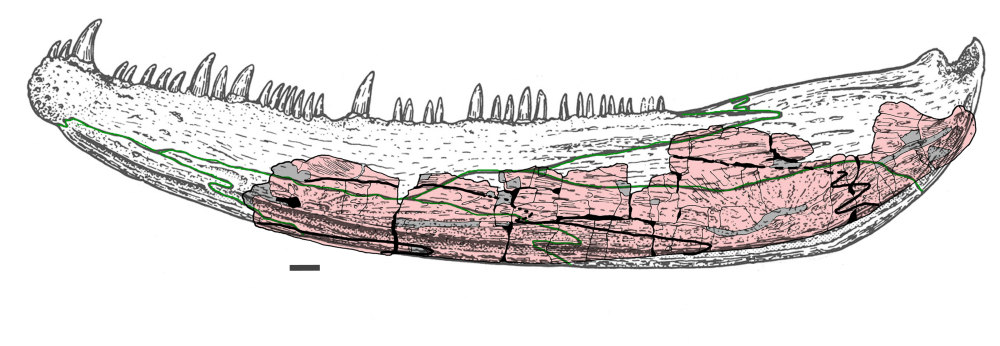

Partial lower jaw of a Crassigyrinus-like animal prepared (ie rock matrix removed) and drawn. Scale bars: 1 cm. © Copyright Jenny Clack 2018

Partial lower jaw of a Crassigyrinus-like animal reconstructed. Pink shows the bits we found. Scale bar: 1 cm. © Copyright Jenny Clack 2018

In 2010, in Bed 383, we found the partial lower jaw of a large tetrapod similar to one known from 20 million years later, called Crassigyrinus scoticus , and although it's not unreasonable to identify the genus as Crassigyrinus, it's unlikely to represent the same species. We also found a few other skull bones at the time, which we didn't realise might be Crassigyrinus, but since then we've found a number of post-cranial elements such as ribs and body scales, and we now think it not impossible that these all came from the same individual. We've not found any more bones like these recently, suggesting that most of the animal's remains had been eroded away before we started collecting.

The lungfish bones we've found also come in a wide range of sizes, from tiny juveniles or small-bodied taxa up to large adults. Two very large lungfish opercula (gill-covers) represent what we think are the largest lungfishes found in the Carboniferous. A rough guide to the length of the fish can be obtained by a ratio of 15:1 from the diameter of the operculum (Tim Smithson, personal observation). By this measure, the large opercula belonged to fish up to three metres in length. Those from the later Carboniferous found so far are no more than about half that size as judged by this ratio.

The rhizodonts we've found are mostly from mid-sized or large individuals, although we do have a few small rhizodont bones, and we think we've got at least two different taxa from Bed 383, though that's not certain yet. One bone, a very large element from the pectoral girdle, suggests a fish of a size comparable with those of the large lungfish.

Rhizodont cleithra (pectoral girdle bones) © Copyright TW:eed Project.

Gyracanth spines are among the most common elements in this bed, though they are difficult to collect and prepare and are often broken. Some elements are exceptionally large, in keeping with the large elements of tetrapods, lungfishes, and rhizodonts. Similar spines, though not as long, were found in the base of the overlying sandstone , although they had been subject to erosion on the surface of the exposed wall. They were lost in the rock fall early in 2018.

Fin spine of a Gyracanth © Copyright TW:eed Project.

We've interpreted the exposure at Burnmouth as a series of meandering river channels, indicated by sandstone beds of varying thicknesses, with periodic inundation by shallow lakes, the latter resulting in thinner dolostone beds. Some interpretation was done using satellite images and aerial photography from a drone with a gimbal-mounted camera.

Fire has been an important influence on the Earth system throughout history. To have a fire, you not only have to have something to burn and a source of ignition (generally lightning), but also enough oxygen in the atmosphere. You need at least 17% atmospheric oxygen. The fact that we have found charcoal in the sediments of this conglomerate tells us that the oxygen level was above that figure. Some years ago there was a theory that the lack of vertebrate fossils in "Romer's Gap" was down to low atmospheric oxygen, but our charcoal disproves that.

Conclusions

We've found large numbers of tetrapods, lungfish, rhizodonts and gyracanths in Bed 383, of a wide range of sizes, from very small to very large, showing that recovery from the Hangenberg extinction event at the end of the Devonian was much quicker than had previously been thought. Low atmospheric oxygen levels are disproved by the presence of charcoal in the sediments, and we've shown that the Tournaisian was not a depauperate stage at all, and that "Romer's Gap" largely resulted from lack of exploration of such localities.

The paper is Open Access, so you can read it online on the PeerJ website.