Palaeontology: A Fish and Tetrapod Fauna from Romer's Gap

Ben Otoo, Jenny Clack, Tim Smithson, Carys Bennett, Tim Kearsey, Mike Coates

The work behind this paper started off as a Masters project for Jenny Clack's student, Ben Otoo at the University of Cambridge, but soon ballooned into a much bigger piece of work. Ben focussed on the vertebrates, but specialists from other institutions contributed to many aspects of the work.

Romer's Gap was a hiatus in the non-marine fossil record that spanned the earliest (Tournaisian) stage of the Carboniferous (~359-345 Ma). Named for the paucity of tetrapod fossils throughout this interval, the gap had long obscured evolutionary events and ecological transitions implied by differences between the few, mostly aquatic, limbed forms present at the end of the Devonian, and the diverse and disparate tetrapods known from the next stage, called the Viséan. Before the gap, tetrapods were largely aquatic; after it, many were fully terrestrial.

What little we did know about Tournaisian tetrapods derived from the isolated bones and footprints from localities such as Blue Beach in Nova Scotia, as well as a single, partially articulated tetrapod from Dumbarton, Scotland, Pederpes. However, the challenge presented by Romer's Gap extended beyond tetrapods; few Tournaisian fish localities had been known until recently, and these, too, appear impoverished relative to subsequent Viséan faunas.

The Tournaisian age Ballagan Formation crops out in northern England and the Midland Valley of Scotland. It is particularly well-exposed at Burnmouth, Scotland, as just over 500 m of vertically dipping beds, laid down over a period of roughly 12 million years. As you walk from the cliffs out towards the sea, so you walk over younger and younger rocks.

Most of the tetrapod fossils at Burnmouth occur from 332-383 m, though there are isolated bones known from lower horizons. The greatest concentration comes from a ~50 cm span within a highly-sampled 1 m interval at 340.5 m originally discovered by Tim Smithson. This 1 m interval contains two beds from which tetrapod fossils have been recovered, and is here designated the Tetrapod Interval Metre, or TIM.

Tim Smithson cutting the TIM © Copyright TW:eed Project.

The beds at Burnmouth are interpreted as representing a range of floodplain environments including woodland, scrubby vegetation and saline marshes, including rivers, ponds and lakes.

Mottled grey siltstones and green palaeosols (fossil soils) represent deposition within a floodplain lake, then the growth of vegetation. Although periods of desiccation occurred in the lower part of the section, in general the soils were waterlogged and the environment was probably a brackish marsh. Sandy siltstones were deposited as cohesive debris flows in flooding events after periods of desiccation.

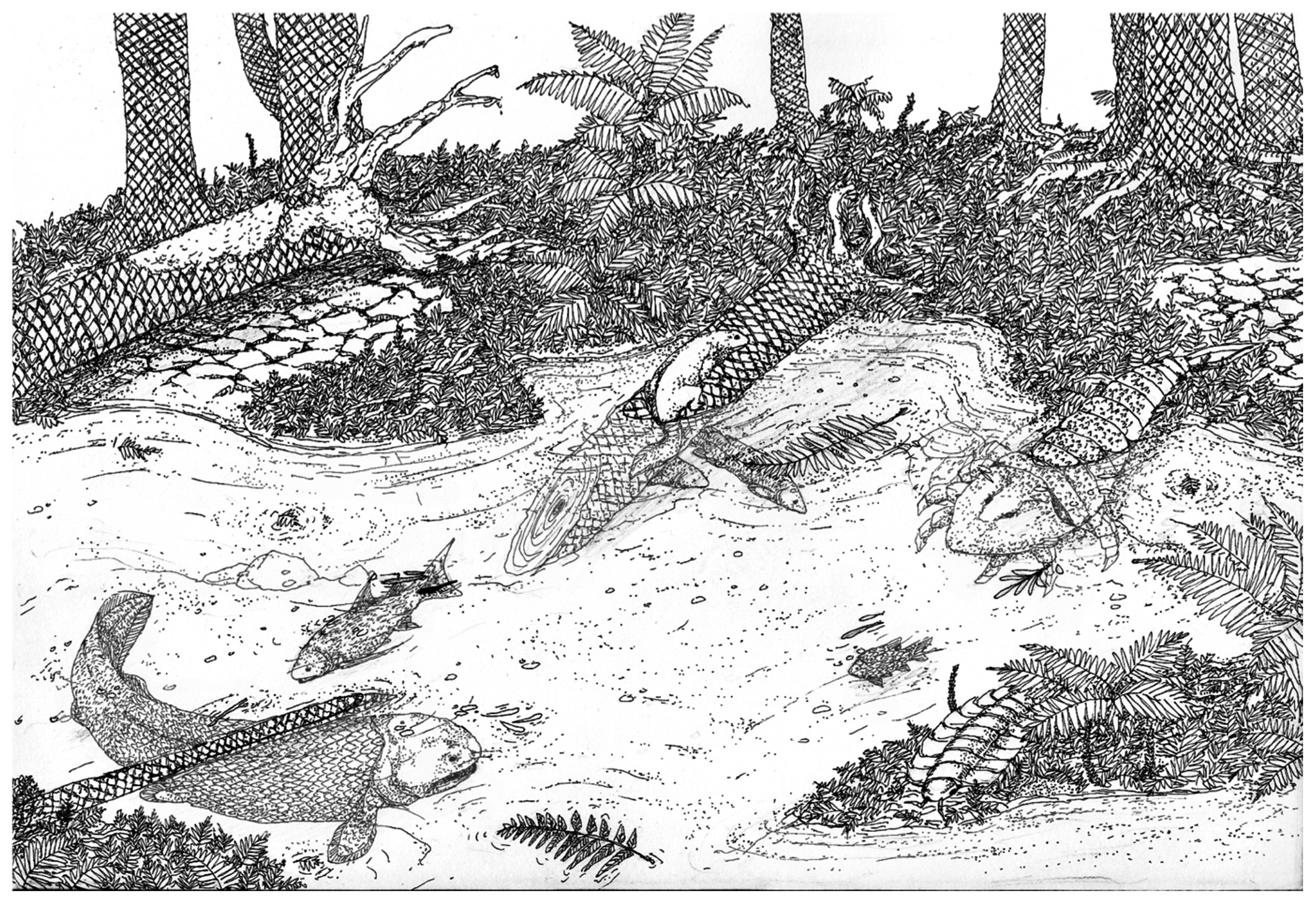

Reconstruction of what we think the environment may have looked like.

Artwork by Yasmin Yonan (University of Leicester, 2015).

To obtain a high-resolution sedimentological and palaeontological data set, the TIM was sampled by removing a 1 m × 1 m × 30 cm block from the foreshore. This was recovered in June 2013, with permission from Crown Estate Scotland and Scotland Natural Heritage. This sample was then systematically broken up and fossils recovered for study, including the use of CT scanning.

The vertebrate fossils recovered from the TIM represent three shark/ray-type fishes, two fishes of a type called rhizodonts, five different types of lungfish, three different tetrapods and a ray-finned fish. One of the tetrapods was found completely by accident, when a rock sample containing visible lungfish bones was CT scanned. It has still not been seen with the naked eye and probably never will be.

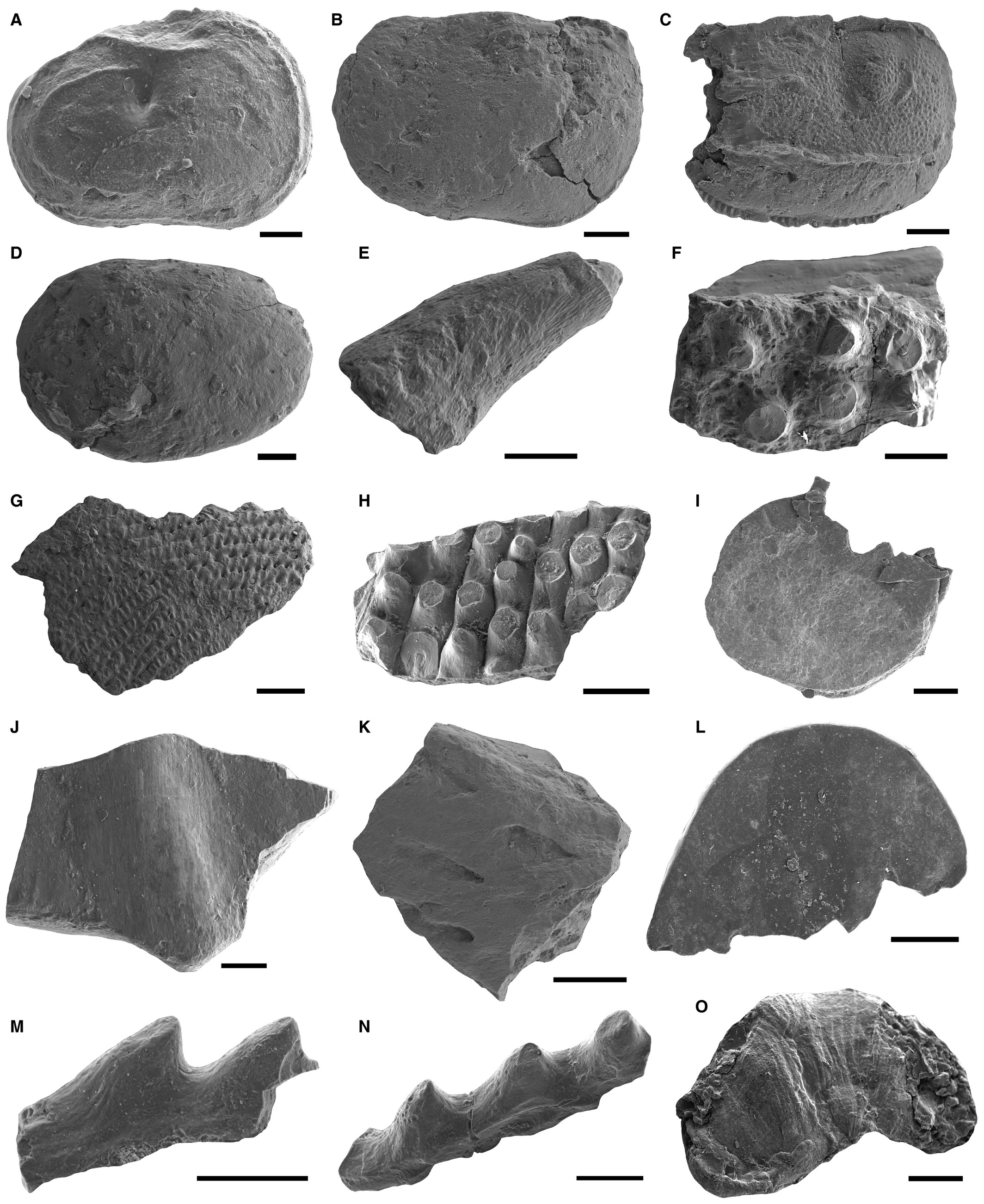

Micropalaeontological analysis was done by dissolving samples of the sediments in acid and sieving using increasingly fine sieves, then picking through the remains under a binocular microscope. Much of this work was done by volunteers at the University of Leicester. The distribution of the microfossils is consistent with that of the larger fossils recovered from the TIM.

A selection of micro-fossils. © Copyright Carys Bennett.

A modern analogue for the dry/wet alternations seen in the palaeosol/sandy siltstone association are mud aggregates in dry land river floodplains. However, the climate of the Ballagan Formation is interpreted as tropical, with seasonal monsoonal rainfall, which is consistent with our understanding that the UK was situated near the equator at the time.

Either ecologically or evolutionarily, this floodplain association may have formed the basis of the coal swamp faunas that characterize many Carboniferous localities. Insofar as the Carboniferous is marked by a diversification of ray-finned fishes and sharks and rays, during the Tournaisian these events may have been happening in different environmental or faunal contexts. Future comparative ecological work will be valuable for understanding these issues.

The paper is Open Access, so you can read it online on the Palaeontology website.