PLoS One: A Diverse Tetrapod Fauna from the base of Romer’s Gap

The Palaeontological Framework team have published their first paper for this project, in the journal PLoS One (Public Library of Science). It's called "A Diverse Tetrapod Fauna from the base of Romer's Gap" and you can read it. This summary is intended for interested non-specialists.

The earliest tetrapods, dating from the Late Devonian, have been much studied recently, and have been shown to have had some unexpected characteristics, such as polydactyly and functional internal gills, suggesting that most were aquatic. These fossils have inspired intensive exploration into the nature of the acquisition of full terrestriality, and various aspects of transitional locomotion are being studied biomechanically and biochemically using such extant models as the actinopterygian fish Polypterus, mudskippers and a number of salamanders.

As explained elsewhere on this site, the transition to full terrestriality seems to have taken place during a period of perceived fossil scarcity; a source of much frustration to vertebrate palaeontologists for many years.

There was a proposal that atmospheric oxygen levels were significantly lower than today, and that this acted as a constraint, preventing tetrapod emergence onto land, but this hypothesis has been criticised because more recent studies have shown that the oxygen levels were not much lower than presently. In any case, the oxygen level in water is dependent on that in the air, so lower oxygen levels would more likely have driven the transition to terrestriality than the reverse. Added to which, fossilisation is much more readily achieved in water than on dry land. You would expect terrestrial tetrapods to be found less frequently than aquatic ones.

For many decades, isolated fossil bones have been collected from a locality called Blue Beach at Horton Bluff, Nova Scotia, but the fact that they were disarticulated made deriving any useful information from them very difficult. The tides in the Bay of Fundy rise and fall a world record 15+ metres, and the fossil-bearing strata are only exposed for a few hours each day. The power of the tides also means that any exposed fossil is rapidly destroyed. Fortunately, joint proprietor of the Blue Beach Fossil Museum and co-author of this paper, Chris Mansky, lives very close by and is able to scour the beach frequently. He has accumulated an impressive collection of material.

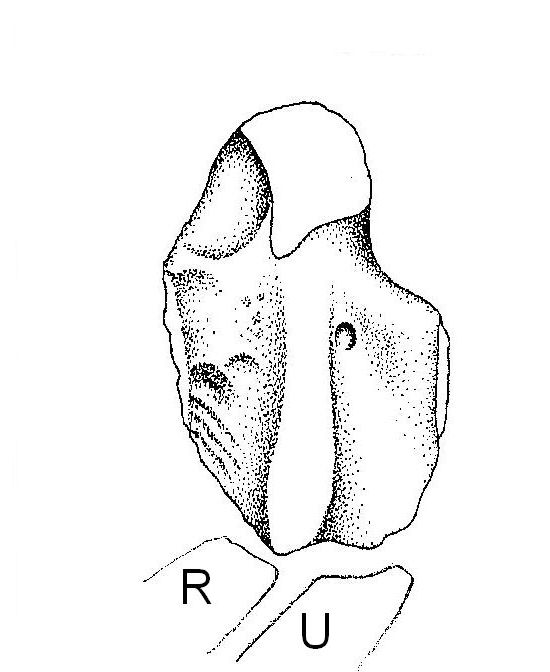

Humerus from Blue Beach

© Copyright 2015 Anderson et al.

These early tetrapods were very different from the ones we're familiar with today, and this humerus (left) from Blue Beach is fairly typical. It's a relatively flat, L-shaped bone, with the shoulder joint at the top and the articulation with the radius and ulna to the left. I've sketched in the approximate positions of the lower arm bones, but that's only to give you an idea of where they'd be, it's not intended to be at all accurate!

Recently, extensive fieldwork in Northumberland and the Scottish Borders has yielded a diverse fauna of tetrapods, fish and some arthropods, suggesting that Romer’s Gap was an artefact of uneven sampling, rather than a reflection of what was going on in the Early Carboniferous. The new specimens have enabled researchers to place some of the Blue Beach specimens into taxonomic context, allowing them to be formally described, that being the subject of this PLoS One paper.

The paper describes three distinct forms of humerus, two of scapulo-coracoid (part of the shoulder girdle), four of femur, two of tibia and two of pelvis. Although isolated, the shapes of some of these bones are fairly distinctive, allowing the authors to estimate taxonomic diversity at the locality. They conclude that there are at least five different types of tetrapod represented, and can infer the presence of several more, based on the extensive sets of trackways which have been collected over the years. The tetrapod fauna was evidently quite rich, in marked contrast to our thinking even fairly recently.

Interestingly, the Blue Beach fauna includes some tetrapods clearly similar to some of the Late Devonian forms, as well as animals more similar to those that appear later in the Carboniferous, and it has been reported that some of these later forms may also be represented by fossils from the Devonian deposits at Red Hill, Pennsylvania. This would suggest that the end-Devonian extinction event might have had less of an impact on the tetrapods than had previously been supposed.

A final, tantalizing implication of these fossils is the question of the timing of the divergence of amphibians and reptiles. Some of the specimens resemble a Late-Devonian form called Tulerpeton, which has similarities to a group of Carboniferous stem amniotes called embolomeres. There is still quite a bit of speculation here, but if this all hangs together, it implies that the reptile-amphibian divergence took place in the Late Devonian, much earlier than previously supposed. This would be consistent with some molecular clock estimates. Clearly, more work on these fossils is required to examine this possibility in more detail.

Here is a video clip of the syncline at Blue Beach, where many of the tetrapod fossils have been found. © 2014 Jason Anderson.