Nature Ecology & Evolution: Phylogenetic and Environmental Context of a Tournaisian Tetrapod Fauna

The main reason we started this project was the perceived dearth of fossils in the earliest part of the Carboniferous period, the Tournaisian and early Viséan, a time represented by very few fossils, not just of tetrapods, but also sharks and rays, lungfishes, ray-finned fishes and arthropods. It was as though there was a mass extinction at the end of the Devonian, and then nothing happened for 20 million years or so. That apparent gap in the fossil record was first identified by the US palaeontologist, Alfred Romer, and was later named Romer's Gap in his honour.

However, we knew that things had been going on during that interval, at least on the tetrapod front, because the Devonian tetrapods that we knew about were pretty much fully aquatic, while many of those appearing immediately after the Romer's Gap were fully terrestrial, some had lost their legs entirely, while yet others had returned to the water to live an aquatic life.

There was a large collection of isolated tetrapod limb and girdle bones, along with numerous footprints, from the Tournaisian of Nova Scotia, but these had not been studied in any depth.

After 25 years of searching, Dr Tim Smithson, and later on professional fossil hunter, the late Stan Wood, found a range of tetrapod, fish and arthropod fossils, which formed the basis of this project. Since then, many more fascinating fossils have been found. We published a paper describing seven new taxa of the lungfishes was in 2015, and another describing a diverse fauna of cartilaginous fishes from slightly higher up in the sequence is in press.

In this paper, we describe five new Tournaisian tetrapods, along with analysis of their relationships, information about the plants, environment and atmospheric conditions. We also have a further seven taxa of tetrapod which are distinct, but not diagnosable at present.

In this summary, I shall omit the technical descriptions as being rather specialised, but talk in more general terms about what we have discovered.

Early in the project, sedimentologists from the University of Leicester and geologists from the British Geological Survey made detailed, fine-resolution logs of the rocks at the main site at Burnmouth, as well as several other localities, and of the core from a borehole which we drilled through nearly 500 metres of sediments near Berwick upon Tweed, to help us correlate the rocks at the various sites.

At Burnmouth in particular, that allowed us to realise that most of the tetrapods had been found in sandy siltstones lying immediately above wetland palaeosols, suggesting they had been living amongst the vegetation on relatively dry land, and their remains were buried by periodic flooding events. As palaeosols are common at Burnmouth, this suggests where we might profitably concentrate future collecting activity.

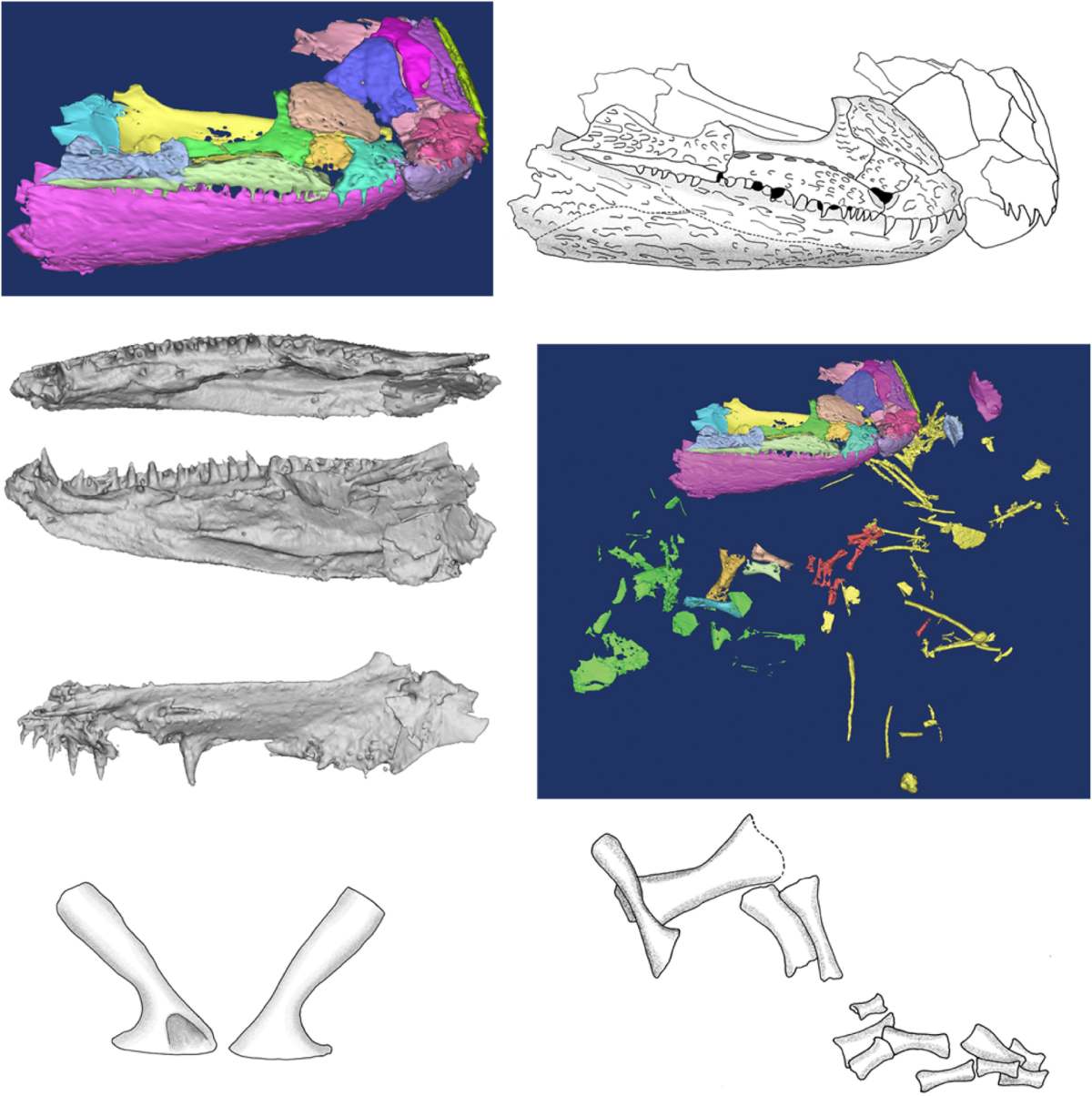

One of the tetrapods was a particularly lucky find. Ben Otoo was working in Cambridge on a metre square section of sediments collected from Burnmouth and saw some lungfish bones sticking out. Wanting to know what was inside before doing any further investigation, he asked Ket Smithson to CT scan the block, and they were amazed to find, not just the lungfish bones they already knew about, but also a partial tetrapod skull, along with some scattered post-cranial material.

This fossil is still only known from the scans, as it is too fragmentary and fragile to extract from the rock matrix. We called it Aytonerpeton microps - Ayton is the name of the parish where it was found, erpeton is from the Greek and means 'crawler' or 'creeping one', micro is Greek for 'small' and ops is the Greek for 'face'.

Aytonerpeton microps © Copyright 2016 Jenny Clack.

Another tetrapod we named Ossirarus kierani. Ossi is Latin for 'bone', and rarus is Latin meaning 'scattered' or 'rare', while kierani honours Betty and Oliver Kieran representing the Burnmouth community, who have supported us and encouraged local interest and cooperation from the start.

Looking at the analysis of relationships, we see that some taxa bear strong similarities to some Devonian taxa, suggesting these lines survived the end-Devonian extinction, while others seem basal to either the line leading to amphibians or else that leading to amniotes, ultimately reptiles, mammals and birds. This amphibian-amniote split is much earlier in the radiation of tetrapods than had previously been thought, but corresponds well with recent molecular analyses which place it at 355 million years ago, only four million years after the end of the Devonian.

The floodplain environments of semi-permanent water bodies, marsh, river banks and areas of dry land with trees were laid down at a time of change in the land plant flora, following the end-Devonian extinctions. The new flora initiated a change in fluvial and floodplain architecture. A group of plants called progymnosperms had been almost eliminated in the extinctions, but thickets and forests were re-established quite early on, with lycopods as the dominant flora. At Burnmouth, several beds with abundant spores of the creeping lycopod Oxroadia include tetrapod fossils. Terrestrial ground-dwelling arthropods, such as myriapods and scorpions, fossils of which have been found at Burnmouth and Willie's Hole, form a possible food supply for the tetrapods.

One of the theories put forward to explain the apparent lack of fossils in the Tournaisian was that atmospheric oxygen levels were low, so to test this, we examined charcoal from the sediments of two of our main sites where it is relatively common.

We analysed 73 samples from Burnmouth and Willie's Hole, and for comparison with wildfire activity before and after Romer's Gap, nine samples from the Upper Devonian of Greenland and 42 samples from slightly higher up in the Carboniferous, from East Fife.

All samples were found to contain between 2% and 2.6% fusinite, a form of charcoal only formed in quite intense fires, indicating that oxygen levels must have been at least 16% throughout the period from the end of the Devonian to the Viséan. The low atmospheric oxygen theory is not consistent with these findings.

Although most of our tetrapods are rather small, none of the five taxa described having a skull length of more than 80 mm, we have found larger specimens at Willie's Hole about a quarter of the way up the sequence and probably three or four million years after the end of the Devonian. This is also consistent with tetrapod trackways, and suggests that while the survivors of the end Devonian extinction event might have been rather small, larger forms evolved quite rapidly.

The wealth and diversity of tetrapod taxa from the Tournaisian clearly demonstrates that the lack of such fossils in our museums is due to inadequate collecting. We really need field workers to get out there and explore or re-explore non-marine Tournaisian deposits, and we're confident that when they start to do that, plenty more material will be found.

It's not open access, so non-subscribers can only read the abstract http://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-016-0002. Sorry about that.